Irish Kilts & Tartan

Hibernean Dress, Caledonian Custom

A brief history of Irish kilts and tartam by Matthew Newsome and Todd Wilkinson (c) 2010

While the traditional tartan kilt is seen generally as an icon of Scottish culture, many people, especially Americans of Irish heritage, also associate the garment with Ireland as that nation’s “traditional dress”. The Internet has only heightened this misconception with all sorts of claims for an ancient pedigree for the kilt & tartan cloth. It is our hope that this brief article will help set the record straight in terms of the origins of the kilt as an Irish garment, as well as the association of tartan with the Emerald Isle.

The Irish Kilt

In his book Life & Tradition of Rural Ireland, Timothy O’Neill discusses the idea of the kilt as a form of Irish national dress. Like other noted scholars such as Henry McClintock and Kass McGann, O’Neill establishes the origin of the Irish kilt at the end of the 19th century in the so-called “Gaelic Revival” movements attempted to create a distinct Irish culture to separate themselves from their English overlords.

Suffice it to say that most scholars of Irish dress agree that the kilt is not part of traditional Irish dress, nor does it have a pedigree in the mists of Irish antiquity. The kilt was adopted by some (but certainly not all) Irish nationalists at the end of the 19th century in an attempt to counteract the Anglicization of Ireland, which had been going on for hundreds of years before.

At the end of the 19th century, a “Gaelic Revival” of sorts began to take place in Ireland as a reaction to British rule. Besides the effort to restore the Irish language, the revival also sought to restore “traditional” Irish culture in many forms, including sports, literature, song and dress. In 1893, for example, the Gaelic League was organized, with Douglas Hyde as its first president. The League’s goal was to preserve Irish as the national language, and to study Gaelic literature, both ancient and modern.

About 10 years before the formation of the Gaelic League, the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) was founded by Michael Cusack to provide an Irish alternative to traditional English sports such as cricket, rugby and polo. While both the League and the GAA were nominally apolitical, both groups began to attract Irish Nationalists of all stripes. And in both organizations, we find individuals looking for the adoption of an Irish “national dress”. (Bottigheimer, pp. 212-214)

But who is responsible for the myth of the Irish kilt? Noted scholar Henry McClintock believes that the idea may have originated with one Eugene O’Curry, Professor of Irish History in the Catholic University of Ireland, who first proposed the idea of the Irish kilt in ancient times in his 1860 Manners and Customs of the Ancient Irish. McClintock also mentions “a well-known antiquarian”, Patrick Weston Joyce, who strongly advocated O’Curry’s claims in his Social History of Ancient Ireland, which was published in 1903. Kass McGann cites McClintock’s claim that Joyce mistranslated the word “Leine”, in reference to an ancient Irish shirt, as “kilt”, in her article “Proof against the Existence of an Irish Kilt”.

In his Old Irish and Highland Dress, McClintock states his belief that it was Joyce’s book that put the idea of an Irish kilt firmly in the minds of many, as the book was “widely read and carried much weight at the time.” (McClintock, 123) Indeed, McClintock believes that it was Joyce that inspired Irish pipe bands to adopt the saffron kilt (which was also mentioned in James Joyce’sUlysses). McClintock is quick to suggest that those who took Joyce and O’Curry at their word were not to be blamed, as they had “what seemed to be ample authority” for adopting the kilt as a form of Irish dress.

Who were these individuals that adopted the kilt? One was Sir Shane Leslie of County Monaghan. Born in 1885, John Randolph Leslie came from a prominent Anglo-Irish family, and attended Eton and King’s College, Cambridge, where he converted to Roman Catholicism, taking the Gaelic name Shane. Leslie became a devoted Irish nationalist as well as Roman Catholic, and adopted the “traditional” Irish saffron kilt, and began a personal campaign to urge the adoption of it in 1906, according to Janet and Gareth Dunleavy’s biography of the Gaelic League’s founder, Douglas Hyde. (p. 317)

A description of Leslie in an article in Time Magazine in February, 1957 describes him as cutting a “glorious Irish swat through London on his visits, tricked out in mutton-chop whiskers, cockaded tam-o-shanter, green kilt and dagger in the stocking.”

Another kilt-wearing Irish nationalist aristocrat was William Gibson, 2nd Baron Ashborne. Like Leslie, Ashborne had been educated at Oxford and Trinity College in Dublin (known for its strong Unionist sympathies). When Ashborne was first admitted to the House of Lords in May, 1913, the New York Times reported that there was great curiosity if he would wear his saffron kilt to Westminster. Such an act might have caused an incident, as some months before, the House of Commons refused to admit an Irishman to the stranger’s gallery because he was wearing a kilt. (May 1913)

When his father, Edward Gibson, 1st Baron Ashborne, died that same year, the New York Times reported that he received only $4,000 from his father’s estate because “he is an enthusiastic Nationalist, wears the ancient Irish dress, and is a convert to Catholicism.” (July 22, 1913).

Another nationalist, who was later killed in the Easter Uprising of 1916, Eamonn Ceannt, wore a kilt when playing the uileann pipes during an audience with the Pope in 1908. (O’Neill, p. 44) Indeed, kilts were quickly adopted by a number of pipers and pipe bands in Ireland in the days before the First World War. Several of these bands are still in existence, including the Black Raven Pipe Band, the St. Laurence O’Toole Pipe Band and the Youghal Pipe Band.

Many of these pipe bands were formed during the renewal of the national game of hurling, as part of the larger “Gaelic Revival” of the late 19th and early 20th century. In the case of the Black Raven Pipe band, it was in connection with the Naomh Mac Cullen Hurling Club of Fingal.

According to the band’s web site, a pipe band that accompanied a rival club from County Armagh made quite the impression on a club member and school teacher named Thomas Ashe, who soon acquired a set of pipes and began to teach himself how to play. In 1910 Ashe began to organize a band and recruit new members. He contacted the noted Belfast antiquarian Mr. F J Bigger to assist with the design of the band’s uniform, which included the kilt.

In 1911, the band paraded for the first time with its new uniform, which included two versions. The first one was a black tunic, green kilt and white plaid shawl. The second uniform was white tunic, saffron kilt and black plaid shawl. The band marched under a reproduction of the Black Raven flag, said to have been captured by the forces of King Brian Boru from the Danes at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014.

The band competed against a number of rival bands in national competitions until 1916, when several of the members joined the Easter Rebellion against British rule. The founder, Thomas Ashe, would die as a result of a hunger strike in prison in 1917.

The history of the Youghal Pipe Band, founded in 1914 by one Danny McCarthy, may have something to tell us about regarding the adoption of the kilt by Irish pipers and nationalists. Youghal, in County Cork, had long been a garrison town for units of the British Army stationed in Ireland; the band’s history reports that McCarthy “would watch the Pipe Bands of the British Army parade their Regiments down Cork Hill and out to the train station every couple of months,” and would also go to the barracks to listen to the bands. Eventually he organized the formation of the Cork Hill Pipe Band, which later renamed itself after the town of Youghal.

McCarthy and several members of the band were members of the Irish Volunteers, a Nationalist paramilitary force which later became the Irish Republican Army during the Anglo-Irish War of 1919-1922. Pipe bands became an important recruiting tool for Nationalist forces; in a biography of IRA leader Terence MacSwiney, Moirin Chavasse discusses how a pipe band was used in October, 1915 as part of a recruiting drive for the Volunteers. (Terence MacSwiney, p.35)

IRA pipe bands even had yearly competitions; The Cork Volunteer Pipe Band was named as the “Prize Pipe Band” in competitions held in Killarney (1918), Cork (1918-1919) Dublin (1920) and Wexford (1922), according to information on the personal genealogical web site of Bryan Wickham. Wickham’s father, Michael, later immigrated to the United States, where he joined the New York Corkmen’s Society Pipe Band.

At least one suggestion was made in 1914 for all members of the Irish Volunteers to wear the kilt; in the organizations’ newspaper of February 14 of that year, one William Royce called for the adoption of the kilt by the volunteers, saying that the only objections to such a move would “come from the skinny-legged, knick-kneed type for whose faulty or undeveloped ‘understandings’ the pants as a covering are a veritable Godsend.” (Kelly, p. 219)

The most famous Irish nationalist associated with the kilt, however, is Patrick Pearse. Like many members of the Gaelic League and the larger Celtic Revival, Pearse (himself the son of an Englishman) sought to distance himself from all things English. Pearse joined the Gaelic League in 1905 and soon took an interest in the Irish educational system. Concerned that Irish children, especially boys, were losing their “Irish” identity in an English-dominated school system, Pearse used his life-savings and borrowed funds to form St. Enda’s School for Boys in 1908. The school offered a bilingual education in English and Gaelic, as well a curriculum in “traditional” Irish culture.

As part of his attempt to restore “Irishness” to the educational system, Pearse wished to adopt “traditional” Irish dress. After viewing a pair of trews, coat and cloak found at Killery in County Sligo, which dates to the early seventeenth century, Pearse wrote to John O’Kelly in October 1900 about his ideas on a potential Irish national dress to be worn at a Gaelic League Feis, or Irish cultural festival:

Frankly I would much rather see you arrayed in a kilt, although it may be less authentic (author’s emphasis) than in a pair of these trews. You would, if you appeared in the latter, run the risk of leading the spectators to imagine that you had forgotten to don your trousers and sallied forth in your draws. This would be fatal to the dignity of a Feis. If you adopt a costume, let it, at all events, have some elements of picturesqueness.( Dunlevy, p. 176)

Pearse eventually did adopt a saffron kilt as a uniform for the boys of St. Enda’s, suggesting to parents that the kilt was “economical, hygienic, and [a] becoming costume for boys” as well as a “distinctly national form of dress.” Pearse also recommended that the garments be Irish made, and directed parents to purchase them at Messrs. M. Meers and Co. of 10 Lower Pembroke Street, Dublin.

What did the boys of St. Enda’s think about the kilt? In his memoir Dublin Made Me, C.S. “Todd” Andrews discusses his personal thoughts on Pearce’s “national dress”. Andrews was relatively unaware of Irish culture or nationalism when he came to St. Enda’s, and offered interesting insights about the school uniform:

A number of the boys in St Enda’s wore kilts. This they probably hated doing and for that reason were all the more ready to resent derogatory remarks about them – remarks which no Dublin boy could resist making and I made them. Between the language, the games and the kilts, I seemed to be always involved in quarrels and was thoroughly unhappy in a situation for which I had no remedy. It would never have occurred to me to complain to the teacher.All schoolboys not accepted by the group are unhappy. My problem was that I did not want to be accepted by the group. I despised them and, from their point I was a ‘stinker’. I did not want to talk Irish, I did not want to play hurling or Gaelic football and I thought kilts were funny. I had only one friend, a London-Irish boy who did not know or want to know Irish any more than I did, who disliked all games and tried to avoid them, and who thought that kilts should be worn only by Scots Highlanders. (author’s emphasis)

(Irish Kilt Society Newsletter, No. 11, November 2004, p. 2)

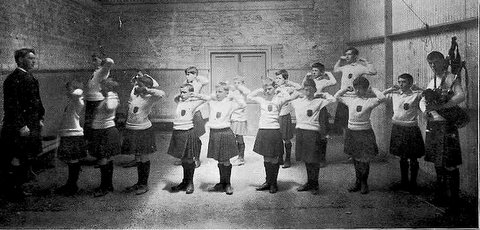

Several photos of St. Enda’s students wearing kilts still exist; one of the most famous shows a group of students engaged in military drill with their instructor, Conn Colbert, who served as physical fitness master for the school. All of the students and Colbert are kilted; the boys wear school jumpers while Colbert wears a brass-buttoned jacket, the official uniform of the Fianna Eireann, the Irish Nationalist Boy Scout organization formed by The Countess Markiewicz in 1909 and named for the ancient Irish warriors lead by the legendary Fionn mac Cumhaill. (Sisson, pp. 125-127)

While kilts were not widely adopted by the Irish, they continued to be worn by pipe bands in the years following the Anglo-Irish War and the Irish Civil War of the early 1920s; Kilt-clad pipers could be found among the Garda Síochána (The Irish Police) and the Irish Defense Forces, as well as among civilian Irish dancers. Even today, the Irish Army and Air Corps maintain pipers in a similar vein to the pipers of the Scottish Regiments of the British Commonwealth. Irish pipers continue to accompany Irish soldiers on United Nations Peacekeeping missions, and their pipes have been heard in such locations as the Congo, Cyprus and Lebanon.

Of course, not all approved of the adoption of the kilt by Irish pipers. In his Irish Minstrels and Musicians, Francis O’Neill, the noted collector of traditional Irish music & Chicago Police Officer, stated in relation to the popularity of the “Scotch” warpipe in Irish circles:

When very young I learned that there was no royal road to Euclid, but there seems to be a royal road to Irish piping. A fellow has only got to get a set of warpipes, hang a kilt around his middle, and throw a bedgown over his shoulders, and he decomes an Irish piper.

(author’s emphasis)(p.478)

Ironically, at the same time that some in the Nationalist community were adopting the kilt, Irish Regiments of the British Army were also seeing pipers in saffron kilts in their ranks. An article from the April 29, 1900 edition of the New York Times discussing the Boer War, mentions a motion in Parliament to kit out the newly-raised Irish Guards regiment in kilts. The article does not take a kind view of such a measure, mentioning the reports from South Africa of the “suffering of the bare-legged Highlanders and of the sorrows attached to this out-of-date uniform.”

The article also criticized the aforementioned Baron Ashborne and his attire, as well as Queen Victoria’s decision in 1900 to allow Irish regiments to wear the Shamrock on St. Patrick’s Day (a custom which continues to present day). The so-called “Shamrock craze”, as the author refers to it, was simply another failure of the English people to “grasp the nature of Ireland’s needs”.

Between the end of the Boer War in 1902 and the First World War, a number of Irish regiments began to add pipers to their muster rolls; in 1909, the Leinster Regiment’s Regimental Journal reported:

The pipers have no distinctive features of dress. (author’s emphasis) They wear dark blue forage caps with scarlet welt band. Their scarlet tunics have white pipe scarlet shoulder straps bearing the regimental title in white embroidery and white piped dark blue collar and cuffs. (Harris, The Irish Regiments 1683-1999, 201).

The journal also gave a description of the first public appearance of the Leinster’s pipers on St. Patrick’s Day of that year; again, no mention was made of kilts at all; however, a photo dated 1919 of the Colonel-in-Chief of the regiment, HRH the Prince of Wales presenting decorations to the men of the 2nd Battalion of the Leinsters shows a Piper J. Fagan clad in a kilt with Scottish style tam-o-shanter. (Harris, p. 202)

In another photo from Harris’s The Irish Regiments 1683-1999, two pipers of the 5th Battalion Donegal Militia, Royal Inskilling Fusiliers (taken in Dover in 1901 when the battalion was preparing to depart for South Africa) are again clad in full-dress scarlet tunic and blue trousers; not a kilt or caubeen in sight. The only odd bit of kit are khaki slouch hats in the Australian style.

Both Harris and David Murphy’s Irish Regiments in the World Wars (Osprey Publishing, 2007) tend to agree that the adoption of saffron kilts by Irish regimental pipers seems to come during the First World War, and before the official authorization of pipers for said regiments. The Irish Guards received their pipers in 1916, and a photo from that year shows the more traditional Irish pipers kit, including saffron kilt.

By the end of the First World War, and in to the 1920s, the “traditional” Irish pipers uniform became fully authorized – in 1927, the Royal Inskilling Fusiliers pipers uniforms contained “as many of the distinctive features of the regiment and ancient Gaelic costumes and decorations as possible.” Of the kilt, the regulations specifically stated: “The saffron kilt, pleated all around.”

By the Second World War, the Irish piper’s costume had become standardized, with saffron kilt, green caubeen and the brat, or cloak. Besides the Royal Irish Regiment of the British Army, the South African Irish Regiment and the Irish Regiment of Canada still maintain pipers and the now traditional Irish uniform today.

Irish Tartans

As one can tell from reading the above, from its inception at the end of the 19th century, the kilt in Ireland has been solid color, generally saffron or green. In fact, the use of solid kilts by Irish pipers has led many to the erroneous assumption that the very concept of a solid kilt is Irish in origin. In actuality, solid kilts have been worn in Scotland for centuries (the earliest depiction of a solid kilt we know of being a portrait of Sir Duncan Campbell of Lochow painted in 1635). Solid kilts in Scotland simply have never been as popular or widely acclaimed as their tartan cousins. Nevertheless, until the fairly recent past, when one spoke of an Irish kilt, it was understood to be solid color. More recently, however, the concept of named tartans, worn in a representative fashion, has made its way into Irish kilt wearing. Perform an internet search today for “Irish tartans” and one will find countless references to the Irish National tartan, tartans for all the Irish counties, and many Irish family tartans. How did this occur?

While the concept of named tartans, worn to represent a particular family or region, is new to Ireland, the use of tartan cloth in a more general sense is not. Archaeological finds give us evidence that tartan cloth was worn in Ireland centuries ago.

The Ulster Tartan

One of the most famous and well-preserved examples is the Dungiven outfit, found near Londonderry in 1956. The outfit consisted of fragments of a cloak, a doublet, and trews made from tartan fabric. The outfit was sent to the Ulster Museum where it was dated c. 1600-1650. It was determined that the trews had likely been tailored in Scotland, but the tartan fabric itself woven in Ireland. (It is worth noting that the Ulster region in Ireland was at this time being settled heavily by Scottish emigrants, so it is at least conceivable that the cloth was woven by a Scottish weaver relocated to Ireland).

Textile expert Audrey Henshall was able to reproduce the tartan pattern for a 1958exhibit; and it is this exhibit that could very well be responsible for the entire “Irish tartan” phenomenon. For it is only after this time that we are able to find anything about named Irish tartans at all. Called “the Ulster tartan,” the pattern was recreated for commercial purposes and promoted with great enthusiasm.

A newspaper clipping in the collection of the Ulster Museum, dated November 4, 1968 (from an unknown paper) mentions that a cloak in the Ulster tartan was presented to theDuchess of Kent during a London fashion show. Another clipping in the same collection, from January 2, 1970, speaks of this tartan being used in ties, table linens, and to “decorate model dollies.”

This tartan first makes its appearance under the name “Tara” being sold to Irish customers in The Kilt Shop in Edinburgh in 1967. Tartan researcher D. C. Stewart notes that it was being sold under the name “Murphy” by the same business to American tourists during the 1977 International Gathering of the Clans. He comments, “It is known that a company called Wexford Weavers were taking some Scottish tartans, changing the colours and giving them Irish names.” Indeed, the Tara/Murphy tartan (which has also been sold under the name “O’Keefe”) is simply the traditional MacLean of Duart tartan rendered in different colors.

Another tartan in the same vein is the Clodagh tartan. The account of this tartan, as related in District Tartans by Dr. D Gordon Teall and Dr. Phil Smith, speaks of a County Tyrone bagpipe maker named Andrew Warnock who wrote to the Scottish Tartans Society in 1979. He claimed at the time that the tartan was called “Clodnaugh Irish,” and that it was an old tartan discovered in the Bog of Allen in southern Ireland. This story has never been substantiated, however (and it is worth considering that it may have been a marketing ploy inspired by the discovery of the Ulster tartan).

The earliest proven date for this tartan is a sample in the collection of the Scottish Tartans Society woven by D. C. Dalgliesh of Selkirk in 1970. It is also worth noting that the Clodagh tartan is a color-variation of the popular Royal Stewart design, which corresponds to the practice noted by D. C. Stewart of weaving firms inventing “Irish” tartans by changing the colors of preexisting Scottish designs.

Following this same practice are the O’Farrell tartan, first documented in 1978 by US tartan researcher William H. Johnston, and the Shaughnessy tartan, designed by Scotch Corner in Gateshead in 2003. Both are Royal Stewart variants. Scotch Corner, in fact, has been the designer of many recent “Irish family” tartans, and seems to be carrying on the tradition of the Wexford Weavers by repurposing traditional Scottish tartans.

Further examples abound, but there is no need to list them each in detail. The fact remains that all of the known Irish family and regional tartans can be dated to some point between the 1960s and today. One can only assume that the enthusiasm surrounding the discovery and promotion of the historic Ulster tartan was the genesis for this surge of Irish tartans.

One also must realize that the idea of named Irish tartans, though perhaps originating in Ulster, has only enjoyed meaningful success outside of Ireland itself. Note the comment of D. C. Stewart, quoted above, remarking that the Murphy tartan was being sold “to American tourists.” And quite a few of these so-called “Irish” tartans were actually produced and marketed by Scottish interests.

Today, without a doubt, the most popular and widely recognized Irish tartans are the Irish County tartans (together with the Irish National) that are produced by the House of Edgar in Perth, Scotland. These were designed in 1996 by Polly Wittering and have since been a major success. More recently still, a new range of tartans for each Irish County (along with a similarly named and similarly colored “Ireland’s National tartan”) has been created by Viking technologies of Glasgow working with Marton Mills of Yorkshire. Both of these lines of Irish county tartans are extremely popular among those of the Irish Diaspora (mainly in the United States) who wish to wear a kilt to honor their “Celtic heritage.”

It is worth noting here that none of the Irish county tartans (from either producer), nor the so-called “national” tartans, have any official standing at all with the Irish government. Nor do most of the Irish family name tartans have any formal provenance with the families. It would appear that many are simply designed on spec, or as requested by a

customer who happens to bear an Irish surname and is looking for a “family tartan.”

There are some Irish tartans that do have a stronger case for recognition. A prime example would be the Cian tartan, which was designed by Ralph and Patricia Saunders for the Clan Cian of Ely and registered with the Chief Herald of Ireland in 1983. One may well ask what the Chief Herald of Ireland has to do with tartan, and that would be a very good question. Nevertheless, this is an example of one Irish tartan that has gained some popularity among the family and seems also to have the approval of a titled head of the family. This fact makes the Cian tartan in the definite minority, however, as far as named Irish tartans are concerned.

Clans Originaux and Pendleton Mill

Readers with some familiarity with Irish tartans may be asking, “But what of the Clans Originaux?” This was long thought to be a book, published in Paris in 1880, and held at Pendleton Woolen Mill in Oregon, which detailed the setts of some early Irish tartans. These included Fitzpatrick, Kiernan, Forde, and many others including the aforementioned Murphy tartan. It was always seen as somewhat of an enigma, suggesting the use of named Irish tartans well before any other established date.

In 2003, Brian Wilton of the Scottish Tartans Authority was able to make contact with Pendleton Woolen Mill and was sent photographs detailing Clans Originaux. What he was able to learn from this informationwas quite nlightening. First of all, this was not an actual published book, but rather a collection of tartan samples – what we would call today a “swatch book” – that would be used in a shop to sell tartan cloth and clothing (in this case, a shop in Paris). But the most amazing discovery was the complete lack of any Irish tartans. Of the some 185 tartans included in the book, all were well known and established Scottish tartans.

Where did the idea come from, then, that this 1880 collection contained Irish tartans? Information on these tartans was passed on to the Scottish Tartans Society by William H. Johnston after a visit he made to Pendleton Mill in 1977. Apparently he recorded details of many tartans with Irish names that were in Pendleton’s collection. He also made notes about Clans Originaux, and somehow his information on Irish tartans was incorrectly attributed to that source in the Scottish Tartans Society archives. It was not until 2003, when Clans Originaux could be formally documented, that the mistake was discovered. Of course by then, theClans Originaux reference and the 1880 date had been repeated in so many sources regarding Irish tartans that this “myth” will be with us for quite some time.

Conclusions

An article from the web site of the Royal Irish Rangers mentions a photo from 1913 of pipers from the 4th Battalion, Royal Irish Fusiliers playing at the funeral of the Duke of Abercorn wearing kilts and “purses” (sporrans). In that same article, the unknown author says of the adoption of the kilt in the Irish regiments, “Who so ever began to introduce a Hibernian dress seems to have leaned heavily on Caledonian custom.” This quote speaks volumes as to the history of Irish kilts & tartans, and serves as a fitting conclusion to this article.

Works Cited

Dunleavy, Janet E and Gareth W. Douglas Hyde: A Maker of Modern Ireland. University of California Press, 1991.

Dunlevy, Mairead. Dress in Ireland. Doughcloyne, Wilton, Cork : Collins Press, 1999.

Harris, R.G. and H.R.G. Wilson. The Irish Regiments, 1883-1999. Sarpedon Publishers, 2000.

Kelly, M.J. The Fenian Ideal and Irish Nationalism, 1882-1916. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 2006.

McClintock, Henry F. Handbook on the Traditional Old Irish Dress. Dundalk, Ireland: Dundalgan Press (W. Tempest) Ltd., 1958.

Murphy, David. Irish regiments in the World Wars. Osprey Publishing, 2007.

O’Neill, Timothy P. Life & Tradition in Rural Ireland. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1977.

Sisson, Elaine. Pearse’s Patriots: St. Edna’s and the Cult of Boyhood. Crosses Green: Cork University Press, 2004.

Websites

www.reconstructinghistory.com

http://www.youghalpipeband.com/history.php

http://www.blackravenpipeband.net/History.html

http://www.slotpb.com/history.shtml

http://www.somebody.to/pp.htm

http://st.louis.irish.tripod.com/

http://www.military.ie/army/specialists/music/pipes.htm

http://royalirishrangers.co.uk/uniform.html

Irish Minstrels and Musicians

The Scottish Tartans Authority

“Sir Shane Leslie, 3rd Bt. (1885-1971)”. Introduction: Leslie Papers. Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, November 2007.

“May Wear His Kilts”. New York Times, May 24, 1913.

“Lethargy in Parliament.” New York Times, April 29, 1900